When I reflect on how I became the philosopher I am today, it seems to me that I underwent four major developments.

The Introduction and Addiction

Philosophy is an intoxicant – for me at any rate. My first exposure to philosophy ignited my imagination, sparking possibility after possibility, each in need of intellectual scrutiny – an activity I, by predisposition, find immensely enjoyable. Drunk with new ideas, even if only half-hatched, I was immediately addicted to philosophy, enjoying myself as I stumbled from one theoretical model to the next. At the same time, I cannot escape doing philosophy; it thrusts itself upon me.

A New Project: Methodology and Rebooting My Beliefs

My second major philosophical development was aided by Descartes and Nietzsche. My initial investigative strategy was to construct arguments for beliefs I already had. However, Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy impressed upon me the backwardness of this approach. Afterall, the beliefs I acquired prior to argumentation could, for all I know, be false. Nietzsche, by revealing to me the extent to which human psychology subverts our capacity to be rational and the extent to which it motivates us to form beliefs in non-truth-preserving ways – even sometimes preferring error over truth – taught me to regard features of myself as being obstacles to knowing the truth, thereby engendering a healthy distrust of what I am naturally inclined to believe. Since my goal was to have true beliefs, Descartes and Nietzsche had these two effects on me. First, I was not to defend my prior beliefs as though they were given to be true. Instead, I was to gather evidence and believe what the evidence entailed or suggested. Second, I was to be wary of being tricked by my own psychology and, as such, be open to the possibility that I may have acquired beliefs in non-truth-preserving manners. It was at this point that I really came into possession of a strong sort of intellectual integrity, one that recognized the importance of methodology in the face of epistemic shortcomings of human beings as limited creatures. At the same time, it caused me to view myself as a philosophical project – something that could be worked on and improved. Specifically, I began situating the will to truth as the central feature of my psychological identity. The initial result of this newly found intellectual integrity and reworking of my psychological identity was a massive upending of my system of beliefs. Thus, philosophy caused in me a deeply personal transformation, one that was exceptionally exciting, but often deeply uncomfortable.

The Awakening: Appreciating the Philosophical Program

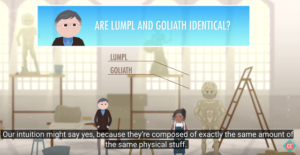

It is unsurprising that those who get a hold of some intellectual integrity admire the sciences and scientific methodology more generally. Afterall, we are taught that the scientific method is emblematic of rationality, and it has certainly proved itself to be a powerful form of investigation. By my lights, however, the awe that the scientific method inspires can all too easily interfere with good philosophical investigation. It did in my case at any rate. In undergrad, I found myself attracted to empiricism, verificationism, physicalism, moral nihilism etc. On reflection, I was attracted to these positions because they, at the time, seemed to me to cohere better either with scientific methodology or with scientific discovery. However, my exposure to the Lumpl/Goliath puzzle radically altered my philosophical trajectory. Moreover, it helped me to more clearly separate the scientific program from the philosophic program, thereby enabling me to conceive the philosophic program more determinately.

For whatever reason, in other puzzles (e.g. the Ship of Theseus), I was willing to deny an intuitive premise in favor of one that committed me to something more scientific sounding (e.g. that the Ship of Theseus was really just an idea caused in us by material being situated in a certain shape, etc, but “the ship” didn’t really exist in the external world). But, in the case of the Lumpl/Goliath puzzle, I could not give up the existence of statues, I could not give up that lumps of clay and statues have differing persistence conditions, and I, therefore, could not give up that Lumpl and Goliath are numerically distinct objects. At the same time, it is wildly counterintuitive to suppose that two concrete objects can occupy the same space. It was the first time I felt the pressure to solve a philosophical problem without appealing to a position that, at face value, sounded scientific. Ultimately, I found myself committed to Goliath possessing immaterial parts or properties that Lumpl does not possess, along with possessing Lumpl as a material part. As a result, I began to better appreciate the various pressures of other philosophical puzzles, and I became more open to the various possibilities of solving a puzzle as being real solutions. Hence, the philosophic program, as a serious means of investigating how the world is, by investigation problems not readily open to the scientific method, became much clearer to me. Eventually, I came to sympathize with (a limited sort of) rationalism, adopt emergentism (or some neohylomorphism), and to adopt moral realism. Moreover, I have become wary of scientific-like attempts to solve philosophical problems, and, when such attempts are made, I am deeply suspicious that the actual problem is, thereby, being ignored or being misunderstood. Of course, I am not saying that scientific results cannot be brought to bear on philosophical problems, but that it must be done so everso carefully.

The Graduate Training

If undergrad ignited my imagination, then graduate school forged my critical faculties. I left undergraduate school terribly intrigued by contemporary metaphysics. This led me to spend a significant amount of time studying under Teresa Robertson. In my experience, Teresa was practically hostile in the face of unclarity. If you were to study under her and communicate with her, you needed to use precise language. And with precise language came clarity of thought. As a result, I replaced the pleasure of drunkenly stumbling through half-hatched ideas with the pleasure of systematically carving out conceptual possibilities, reviewing them in tandem with other commitments, and using logic to whittle down the possibilities to the most probable candidates.

I studied most under Scott Jenkins, as I retained scholarly interests in Nietzsche, Kant, and the early moderns. While Scott also demanded clarity, albeit in a more gentle fashion than Teresa, his pedagogy is what has left the most enduring effect upon me, at least in terms of improving my mind for philosophic investigation. Scott’s pedagogy is Socratic in nature, ‘Socratic’ in the sense of how Socrates teaches the slave boy in Meno. In this way, Scott always acted as a guide in discovering the knowledge within myself (or, less platonically, for myself). This process impressed upon me an important means for learning by myself, and for developing my own accounts of such-and-such without the undue influence of other accounts. Furthermore, it serves as a pedagogical model for me to aspire to as I mentor students going forward.

Under Scott and Teresa’s tutelage, I have developed the critical faculties that are necessary for good philosophical investigation, whatever particular philosophical topic I am contemplating.